The Sun: Energy Source of the Solar System

The Sun is the central star of our solar system and the primary energy source essential for dynamic processes and life on Earth. Classified as a G2V main-sequence star – a Yellow Dwarf the Sun dictates the structure of the system through its gravitational dominance and electromagnetic radiation output. Its stellar composition primarily consists of hydrogen (approximately 74 % by mass) and helium (approximately 24 % by mass), supplemented by trace amounts of heavier elements such as oxygen, carbon, neon, and iron.

Energy production is sustained by nuclear fusion within the Sun’s core, where hydrogen atoms are converted into helium, releasing immense amounts of energy. This energy is radiated into space as light and thermal energy, regulating Earth’s climate and atmospheric circulation while enabling photosynthesis in plant life.

Key Solar Parameters

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Diameter | 1,391,016 km |

| Mass | 1.989*10^30 kg (approx. 333,000 Earth masses) |

| Surface Temperature | approx. 5,778 K (approx. 5,500 °C) |

| Core Temperature | approx. 15 million K |

| Luminosity | 3.828*10^26 Watts |

| Age | approx. 4.6 billion years |

| Distance from Earth | approx. 149.6 million km (1 AU) |

| Rotation Period (Equator) | approx. 25 days |

| Rotation Period (Poles) | approx. 35 days |

| Spectral Class | G2V |

The Sun’s Structure: Layers, Dynamics, and the Coronal Mystery

The Sun is divided into distinct zones and layers. There are two main zones: the internal structure, that is responsible for energy generation and transport, and the outer atmosphere, where solar radiation is effectively released into space and active phenomena occur. For a comprehensive scientific deep dive into the solar engine and the magnetic processes driving our star, explore our dedicated guide on the Layers of the Sun.

I. Internal Structure of the Sun

The internal structure comprises the Core, the Radiative Zone, and the Convective Zone. Each layer plays a specific and vital role in successfully transporting the energy created at the center outwards.

1. The Core

The Core is the Sun’s powerhouse, located at its very center. This is the region where nuclear fusion takes place, converting hydrogen nuclei into helium under extreme conditions. This process releases massive amounts of energy in the form of gamma rays, which sustains the Sun’s entire luminosity.

- Temperature and Pressure: Temperatures reach approximately 15 million Kelvin (K), and the pressure is about 250 billion times greater than Earth’s atmospheric pressure.

- Energy Production: Fusion primarily occurs via the Proton-Proton Chain, effectively converting four hydrogen nuclei into one helium nucleus.

2. The Radiative Zone

Surrounding the Core, the Radiative Zone extends up to about 70% of the solar radius. Energy is predominantly transported through radiation in this region. Photons (light particles) travel slowly outwards, but due to the high density of the matter, they are continually absorbed and re-emitted.

- Energy Transport Time: The average free path of a photon is extremely short. Consequently, the energy transfer through this dense zone can take anywhere from tens of thousands to millions of years before it reaches the next layer.

- Temperature Gradient: The temperature gradually decreases from approximately 7 million K at the core boundary to about 2 million K at the outer limit.

3. The Convective Zone

Making up the outer 30% of the Sun’s radius, the energy in the Convective Zone is primarily transported by convection. Hot plasma rises from the interior, cools at the surface, and sinks back down—a turbulent process similar to boiling water.

- Transport Mechanism: The strong currents of rising and falling plasma are the direct driving force behind the Granulation observed on the visible solar surface.

- Magnetic Field Generation: The turbulent motion of plasma in this zone is fundamental to generating the solar magnetic field and, subsequently, the level of solar activity.

II. The Outer Atmosphere of the Sun

The outer atmosphere consists of the Photosphere, the Chromosphere, and the Corona.

4. The Photosphere

The Photosphere is the Sun’s visible surface, measuring only about 500 km thick. It is defined as the layer from which the Sun’s thermal radiation (light) is finally released into space.

- Temperature: The Photosphere’s effective temperature is about 5,778 K.

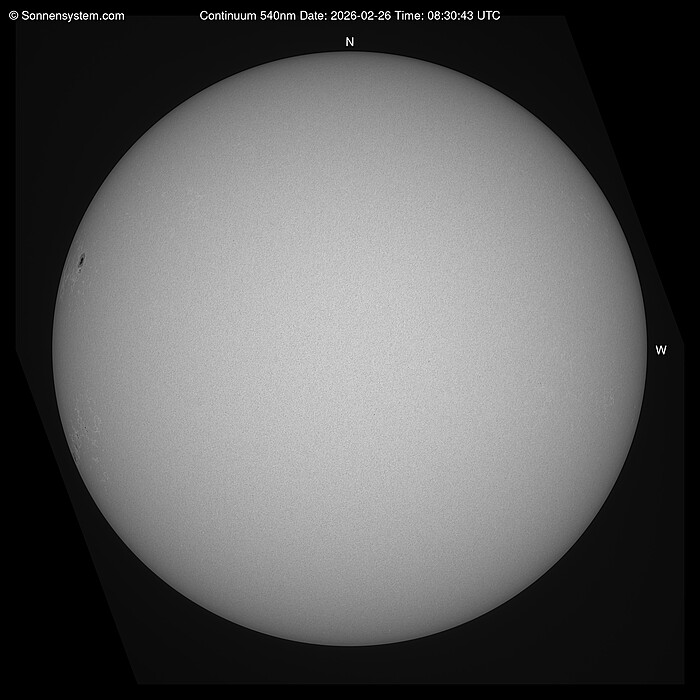

- Phenomena: Characteristic features include Sunspots—cooler, darker regions suppressed by intense magnetic fields—and Granulation, which are the tops of the rising convection currents from the zone below.

5. The Chromosphere

Located directly above the Photosphere, the Chromosphere extends 2,000 to 3,000 km upwards. Normally invisible due to the brightness of the Photosphere, it appears as a thin, reddish ring during a total solar eclipse (hence its name, meaning “color sphere”).

- Temperature Rise: The temperature unexpectedly increases in this layer, rising from the Photosphere to up to 10,000 K.

- Structures: Typical structures include Spicules (jet-like gas bursts) and huge, magnetically supported gas features called Prominences.

6. The Corona (The Sun’s Crown)

The Corona is the highly diffuse and extremely extended outermost atmosphere of the Sun, stretching millions of kilometers into space. It is only clearly visible during total solar eclipses.

- Extreme Temperature: The temperature in the Corona is exceptionally high, reaching values up to 3 million Kelvin. This increasing temperature away from the cooler surface is one of the biggest unsolved mysteries in solar physics.

- Solar Wind Origin: The Corona is the source of the Solar Wind, a continuous stream of charged particles that flows throughout the entire solar system.

III. The Coronal Mystery: Research and Astrophysics

The Solar Corona is a major focal point for astrophysical study due to its extreme properties and dynamic activity.

- The Coronal Temperature Problem: The vast temperature anomaly is a core puzzle. A leading explanation is Magnetic Reconnection, a mechanism where the magnetic fields in the Corona suddenly reconfigure, releasing enormous bursts of energy that superheat the plasma.

- Space Weather Driver: The Corona is the origin of the Solar Wind and the site of powerful explosions known as Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs). These CMEs eject immense volumes of solar plasma into space, capable of causing geomagnetic storms on Earth that can disrupt satellites and power infrastructure.

Current Research Missions

Investigating the Corona requires specialized spacecraft that can withstand extreme environments:

- Parker Solar Probe (NASA, since 2018): This ambitious mission is making the closest approaches to the Sun in history (within about 6 million kilometers), taking direct measurements of the Corona’s fields and particles to solve the heating problem.

- Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO, ESA/NASA, since 1995): SOHO provides essential, continuous monitoring of the Corona and the Solar Wind, aiding in the prediction of Earth-directed CMEs.

- Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO, NASA, since 2010): SDO delivers high-resolution, continuous images of the Corona, helping scientists understand the complex mechanisms behind solar eruptions.

- Hinode (JAXA, since 2006): This Japanese mission focuses on the magnetic field of the Sun, providing valuable data on the processes contributing to coronal heating.

Solar Activity and Space Weather

Solar activity follows an approximate 11-year cycle, characterized by variations in sunspot numbers. The associated phenomena, including solar flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs), are the primary drivers of space weather and can also result in polar lights (Aurora) when they hit Earth’s magnetic field. These energetic events can trigger geomagnetic storms that impact satellites, communications systems, and terrestrial power grids.

The Solar Evolutionary Trajectory

The Sun is currently in the stable main-sequence phase, approximately halfway through its lifespan. In about 5 billion years, the core hydrogen fuel will be depleted. This depletion will initiate the Sun’s expansion into a Red Giant before it eventually sheds its outer layers to form a planetary nebula, leaving behind a dense, faint White Dwarf.