Overview of Magnetic Complexity

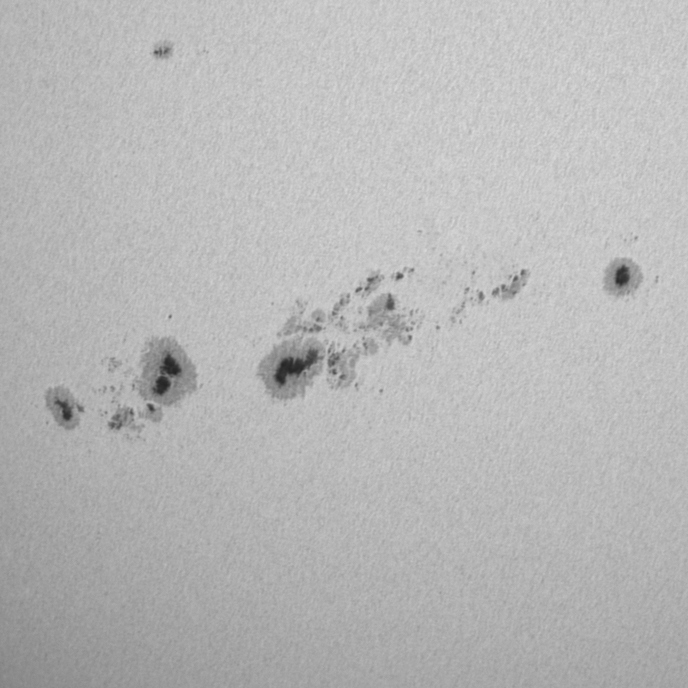

The solar disk currently exhibits a significant concentration of magnetic activity centered around the combined active regions AR 4294, AR 4296, and AR 4298. This clustering of large sunspot groups represents a region of high magnetic flux and topological complexity. The interaction between these distinct active regions increases the statistical probability of significant space weather events, including X-class solar flares and Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs).

To understand the potential output of this system, it is necessary to examine the underlying magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) governing the solar atmosphere.

Thermal and Magnetic Structure of Sunspots

Sunspots appear as dark features on the solar disk due to a temperature contrast with the surrounding photosphere. While the photosphere maintains an effective temperature of approximately 5,800 K, sunspot umbrae are significantly cooler, averaging 3,500 K. This temperature deficit is induced by intense, localized magnetic fields—often exceeding 2,500 Gauss—which inhibit the convective transport of heat from the solar interior to the surface.

Structurally, a sunspot is divided into two primary zones:

- The Umbra: The central, darkest region where the magnetic field lines are oriented vertically (perpendicular to the surface) and magnetic flux density is highest.

- The Penumbra: The lighter, filamentary outer ring where the magnetic field is more inclined relative to the surface.

Magnetic Topology: The Beta-Gamma-Delta Configuration

The potential for solar flaring is directly correlated with the magnetic complexity of an active region. The AR 4294-98 complex is currently classified with a Beta-Gamma-Delta magnetic configuration, indicating a highly unstable topology.

- Beta-Gamma: Signifies a bipolar group where the separation between positive (north) and negative (south) polarities is indistinct or complex.

- Delta Class: This is the most critical classification for high-energy events. A Delta configuration is defined by the presence of umbrae of opposite magnetic polarity within a single shared penumbra.

In a Delta region, magnetic field lines are heavily sheared and twisted in close proximity. This non-potential magnetic field configuration stores vast amounts of potential energy. When the magnetic shear exceeds a critical threshold, the fields undergo magnetic reconnection, relaxing into a lower energy state and releasing the stored energy as radiation (flares) and kinetic energy (CMEs).

Solar Flares and Ionospheric Impact

Magnetic reconnection results in a solar flare, characterized by a rapid increase in electromagnetic radiation. Flares are classified based on their peak X-ray flux in the 1 to 8 Angstrom wavelength range:

- C-Class: Minor events with negligible terrestrial impact.

- M-Class: Moderate events capable of causing brief radio blackouts in Earth’s polar regions.

- X-Class: Major events >10^-4 W/m² capable of triggering planet-wide radio blackouts and long-duration solar radiation storms.

Due to the high magnetic shear in the AR 4294-98 complex, the probability of X-class flaring remains elevated. Since electromagnetic radiation travels at the speed of light, the ionization effects on Earth’s ionosphere occur approximately 8 minutes after the reconnection event.

Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs) and Geoeffectiveness

Distinct from the electromagnetic flare, a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) is the expulsion of solar plasma and embedded magnetic fields into the heliosphere. A CME consists of billions of tons of electrons, protons, and heavier ions.

If the AR 4294-98 complex launches a CME on a geoeffective trajectory, the transit time to Earth typically ranges from 15 to 72 hours. The intensity of the resulting geomagnetic storm is largely dependent on the orientation of the CME’s magnetic field, specifically the Bz component (vertical component relative to the ecliptic).

- Northward Bz: The interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) is parallel to Earth’s magnetosphere, often resulting in minimal interaction.

- Southward Bz: The IMF is antiparallel to Earth’s magnetosphere. This facilitates magnetic reconnection at the dayside magnetopause, allowing solar wind energy and plasma to effectively couple with and enter the magnetosphere.

Geomagnetic Storms and Auroral Mechanisms

When a CME with a sustained southward Bz component impacts Earth, it compresses the magnetosphere and triggers a geomagnetic storm. One of the most visible results is the Aurora Borealis (Northern Lights) and Aurora Australis (Southern Lights).

As solar wind particles are accelerated along Earth’s magnetic field lines toward the poles, they collide with atoms in the upper atmosphere (thermosphere). These collisions excite the atmospheric gases, causing them to emit light at specific wavelengths:

- Oxygen at lower altitudes (approx. 100-300 km) emits green light (557.7 nm), the most common color.

- Oxygen at higher altitudes (above 300 km) emits red light (630.0 nm).

- Nitrogen molecules emit blue or purple light and are typically seen at the lower edges of auroral curtains.

Sympathetic Flaring and Critical Infrastructure

The proximity of three large active regions creates a risk of sympathetic flaring, a phenomenon where a flare or eruption in one region (e.g., AR 4294) destabilizes the magnetic loops in an adjacent region (e.g., AR 4296), triggering a secondary event.

Historically, complex clusters like this have been responsible for extreme space weather events, such as the Carrington Event of 1859. In the modern era, a recurrence of such an event poses risks to Ground Induced Currents (GICs) in high-voltage power grids, degradation of GPS/GNSS signal integrity, and increased atmospheric drag on low-Earth orbit satellites. Continuous monitoring of the magnetic flux emergence in AR 4294-98 is essential for accurate forecasting and infrastructure mitigation.